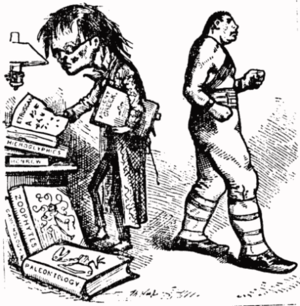

| An intellectual contrasted with a prize-fighter; by Thomas Nast ca. 1875 (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

An old trick that many people learn is to invert or flip a question or problem to better appreciate and dig into it. That is to say, by thinking about why something doesn't matter can help in appreciating if and how it does.

There are many finely written articles and essays the perennially appear about how the academy is under assault by corporatization, the bloat of university versions of mid-level managers, and those with degrees specifically in higher education who wind up in the administration of said institutions of higher learning. Not to mention the problems with student loans, ballooning tuition, and an anti-intellectual political climate associated with certain strands of conservative ideology.

These erudite publications talk about the value of a life of the mind, of having centers of intellectual freedom, and the oft neglected core values and insights so important to human development offered by unappreciated areas of academic inquiry such as the humanities. After all, philosophy and the arts can be considered the grandparents of mathematics and science (whether they be physical, natural, or social). And who can deny the importance of cultivating an appreciation of an examined life, of beauty, of ethics? Especially given the ready examples of psychological stress, anomie, superficiality, and corruption which haunt and seem to point to a hollowness in our societal soul that reality television, celebrity gossip, and hateful rhetoric masquerading as political discourse cannot fill.

These are all solid observations that, while not all irrefutable or uncontroversial, can and have been argued forcefully and eloquently.

So what are the arguments, then that academia doesn't matter?

1. College degrees are used as a form of credentialism that is suffering from massive inflation.

Credentials are outward signs of social status that tell others you deserve access to places and opportunities that are otherwise restricted. For example, people may talk about a time when a high school diploma "really meant something", or that a Bachelor's degree is now the new high school diploma, with a Master's degree having taken on the significance that used to be associated with the Bachelor's.

Credentialism can also be seen in the varying perceived worth of such a degree based on the institution from which it was granted. The value of a degree from an Ivy League school in terms of status and access is much greater than that of a local state school with a mediocre reputation regardless of the actual amount of knowledge or experience gained at either.

The more elite colleges and universities, which include those of the small selective liberal arts variety, can serve to either justify the social status of students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds or raise the potential status of those from lower ones. This is why grade inflation can be such a problem -- to receive a less than stellar mark is a sign of inadequacy.

At other colleges and universities, grade inflation can also be a problem, especially if there is a push for higher enrollment and greater retention rates, which means that there will be pressure to pass more students and to do so with higher grades. Lower enrollment can spell lower revenue and this is a problem as these institutions are being run more and more like businesses and touting new buildings, extra-curricular programs, and a bright economic future to their potential students.

All of this begs the question of the perception and the reality of what colleges and universities are expected to offer and what they do offer. Is university just a time to party while earning your ticket to a better life? Is it a part of an extended adolescence before facing the real world? Is it just "what everyone does after high school"? Is it a time for intensive skill and knowledge training that weeds out the under-performers for post-graduation job recruiters? An opportunity to explore yourself and your world and grow as a confident, educated, engaged member of a global community?

And which of these do the students want and expect?

2. College degrees are being sold as products to get better jobs.

This is a great sales pitch, and many who favor the notion of academia as a place where students will grow and explore intellectually and socially to become better informed and engaged human beings are uncomfortable with it. The implication of students being seen as customers greatly undermines a necessary attitude on the part of students and instructors in which students, especially freshman, respect and trust those with greater knowledge and experience and learn to explore and challenge their assumptions (and eventually even their instructors) in civil and constructive ways.

While too much authority can go to ones head, including professors, there must be enough of it for a student to surrender part of their own certainty and especially their time within and outside of class to fully consider what they are being taught. If you think you know everything (or enough) and see no reason to give someone else your respectful attention if they are keeping you entertained (or frightened), then your chances of learning are greatly diminished.

Moreover, students are going to see some classes as obstacles to overcome by any means necessary and grades as a negotiable outcome rather than as a result of meeting required standards of demonstrated mastery of relevant material. In less formal terms, I am talking here about increases in cheating and what is known as "grade-grubbing". This kind of atmosphere is neither enjoyable or rewarding for professor or student. It also fails to acknowledge that the reason so many jobs and professional programs require a Bachelor's degree precisely because of the assumption about the maturity, ethical qualities, capacity to meet challenges, and persistence that graduates will possess in addition to the particular knowledge and accomplishments are peculiar to a particular major.

Even if one doesn't agree with or care about the aforementioned concerns, the rising costs of highers education, the student loan debt crisis, and an economy that is increasingly unkind to new college graduates mean that the sale of higher ed as a good economic investment are going to be greeted with increasing skepticism.

3. Academic standards are falling.

The validity of this concern depends on how broadly one wants to generalize and what measurement one uses for assessing academic standards. In many ways, when this is used anecdotally or without reference to specific measures of effort, quality or work, assessments of knowledge, and the like, it tends to refer to many of the same problems associated with college degrees being sold as career enhancers. But that is not to say that there isn't concern about how much actual academic work students are doing, the quality of the work, and just how much they are actually learning in the process.

4. Colleges overly pre-occupied with money and status.

This can be seen in many ways, especially the desire for higher ranks in surveys of quality colleges and universities and the focus on income derived from grant-based research. Those academic disciplines and schools that enhance prestige and bring in the research money have much greater influence and security from budget cuts and restructuring than those programs which are not as "productive" in such areas.

Do areas which happen to bring in more money or more acclaim at a given time necessarily have more academic value in terms of a well-rounded curriculum or a culture of intellectual inquiry? This gets back to operating institutions of higher educations like corporations, and raises the question of what is risked the more that college and university administrators do so. Nor should the blame be left solely in their doorsteps. They can be just as frustrated and concerned as the faculty and students, but they may lack the vision or opportunity to liberate themselves and their institutions from such models of operation.

Given the value of these institutions to society at large, a broad conversation about the value, purpose, and future of higher education is sorely needed.

5. Academia is limiting rather than enhancing opportunities for scholars.

This is probably the most controversial of the arguments about the diminished value of academia. It comes in many forms, a few of which I will highlight here.

The first is that the old "publish or perish" paradigm has turned inward and is eating itself. Academics are pressured to publish results in more increasingly splintered, specialized, and obscure journals in order to maintain a respectable looking CV (a.k.a. curriculum vitae, the academic version of a resume). That isn't to say authors and editors are unconcerned with relevance, but the imperative to publish can still skew the results. How much better might the work have been if there had been more time for deliberation and speculation? And who reads some of these journals? What impact do some of these articles really have?

These are not idle questions, and publishers use various algorithms measuring things such as how often articles appearing in their journals are cited, where, and by whom to rank their publications by authority and relevance. The proliferation of journals also has some universities wondering how they are going to keep paying for so many journal subscriptions and wondering which are useful and necessary which can be dropped.

The second reason is that with so many journals publishing so many specialized segments of research studies, scholars can find themselves more and more isolated from people outside of their own sub-discipline despite the great enthusiasm for interdisciplinary approaches and collaborations. Even within some sub-disciplines it can be challenging for groups with different focuses to read and appreciate the sense or value of the work of their peers.

Perhaps a new type of journal by systematic and broadly trained scholars, who can help generalize and synthesize these disparate pockets of research. As someone who was educated in anthropology, anatomy, osteology, human evolution, evolutionary theory, primate taxonomy, paleontology, and smatterings of development biology, physiology, and the history and philosophy of science (and who has taught cultural anthropology, gross anatomy, forensic anthropology, physical anthropology, medical anthropology, primate behavior, archeology, sociology, deviance and social control, and anatomy and physiology), and who really loves such synthesis and exploration, I at least can certainly hope so!

A third is that many scholars who teach more than research either be preference, job requirements, or other circumstances find themselves increasingly devalued on the academic job market, with preference sometimes going to those with less teaching experience and more publications (see argument four above to ponder some reasons for this). These teacher-scholars may be just as informed and engaged with their discipline and when they publish it may be a high quality publication of value to their academic community, but they are much more limited in terms of finding employment, obtaining promotions, and earning the respect of their peers.

The Need for Change

The fact is that academia does have value, but the arguments listed indicate a clash between changing trends and entrenched patterns which threaten to diminish and tarnish its value. An honest appraisal of the purpose and value of academia, how it is structured, and the acceptable roles for scholars is urgently needed.

The roles of edification and personal growth, stimulating intellectual curiosity and discovery, promoting awareness and appreciation of diversity, solving problems with advanced knowledge and technology, and career preparation need to be assessed in terms of how they should fit together and how they should be managed.

The roles and opportunities of trained scholars both inside and outside of the systems of higher education must be reconsidered. Their value and their connections within and without of academia need to be strengthened and recognized and networks should be developed for making sure their talents and experience do not go to waste. A public discussion about the value of higher education and the importance of funding more scholars to work either within academia or in partnerships with government agencies, non-profits, and private industry need to take place in the context not only of its economic worth but of its value to society as a whole to keep such highly intelligent, resourceful, and hard working individuals engaged and productive.

What do you think? Does academia matter? And if so, what must we do to protect and and enhance it?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are very welcome! Just keep in mind that unsigned comments ("anonymous" people please sign in the text of your comment), spam, and abusive comments will be deleted.